Ginia and Guido, Amelia and Poli, Oreste, Pieretto... The characters from Cesare Pavese's two novels The Beautiful Summer and The Devil in the Hills dialogue in alternating editing, overlapping and intermingling Pavese's works in a single flow through the voices and faces of the students of an arts high school.

Biography

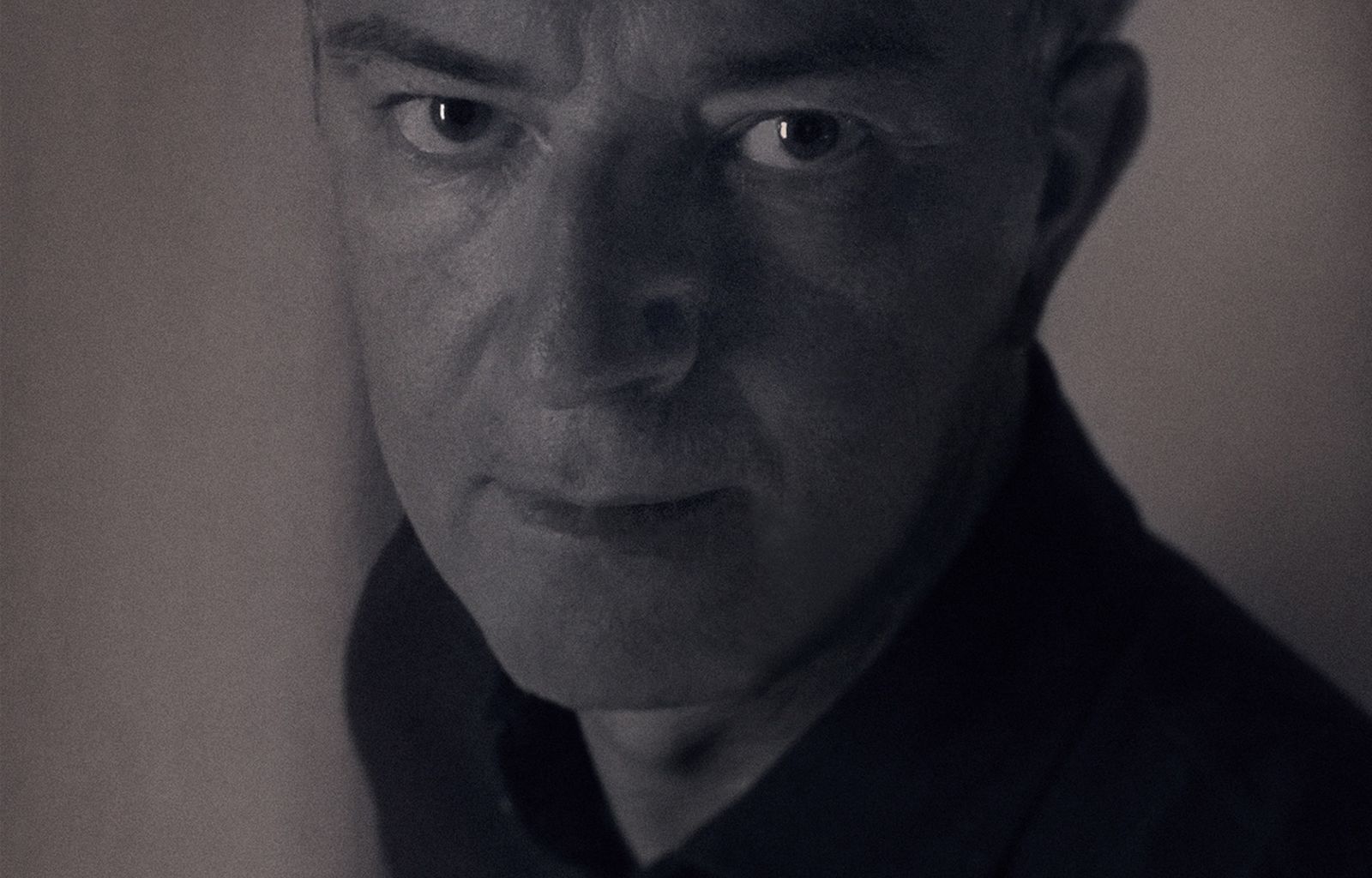

film director

Mauro Santini

(Fano, Italy, 1965), since 2000, has been making films without using a screenplay, recording daily life in diary form. This method gave rise to the seriesof Videodiari, first-person visual stories tied to time and memory; one of them, Da lontano, won in 2002 the section Spazio Italia of Torino Film Festival. In 2006, TFF selected Flòr da Baixa for its international feature film competition. In 2012, he took part in the Cinema corsaro project with his medium-length movie Il fiume, a ritroso (Rome Film Festival) and the feature Carmela, salvata dai filibustieri, codirected by Giovanni Maderna (Venice Film Festival, Giornate degli autori). In 2013, he presented Attesa di un’estate at the Locarno Film Festival. His short Megrez has selected at TFF in 2019.

FILMOGRAFIA

Dove sono stato (cm, 2000), Videodiari (mm, 2001/2003), Flòr da Baixa (lm, 2006)

Un jour à Marseille (mm, 2006), Dove non siamo stati (cm, 2010), Carmela, salvata dai filibustieri (lm, 2012), Il fiume, a ritroso (mm, 2012) Le vacanze (mm, 2013/2018),

Giorno di scuola (lm, 2020), Vaghe stelle (mm, 2018/2023), Le passeggiate (lm, 2018/2023), Le belle estati (lm, 2023)

Declaration

film director

“The movie is like a game of mirrors between 'the beautiful summers' of the young people in the two novels and those of the students who helped make the movie. It's also proof that young people still feel that these topics address them and are up-to-date, over seventy years after the novels were written. Le belle estati isn't fiction, a staging of the two novels; it's a documentary. To be more precise, it is a document of how the students turn themselves into the movie (which is why they read Pavese's book, they don't act it out). The project was also an opportunity for shared reflection on the paths to follow for a type of cinema that can call itself contemporary. My proposal is a type of cinema that reflects on itself and unmasks the act of its creation. The result is a joyful and pleasant game, both belief in the mise-en-scène and a continuous exposure of its fragilities, giving priority to the emphasis of reality.”